Gaps In The Laws Between Property Law and Gender Based Violence of Economic Abuse.

How women are failed by the Justice System that discriminates against them and operates on misogyny and bias.

Spanish Law and Psychological Abuse

Ley Orgánica 1/2004, Spain’s comprehensive law against gender violence, explicitly recognises psychological violence as a form of abuse. It’s also addressed in the Spanish Penal Code, which criminalises habitual psychological mistreatment in a domestic setting. The law covers women in married and non-married relationships with or without cohabitation.

According to legal precedents, psychological abuse includes acts that cause devaluation, emotional suffering, and a climate of fear, such as:

- Threats and intimidation.

- Constant control and manipulation.

- Humiliation and belittling.

- Systematic isolation and disparagement.

The Nexus of Civil and Criminal Law: The justice system compartmentalises cases. The “juicio de desahucio por precario” (precarious eviction trial) is a civil matter focused on property rights, while gender violence is a criminal matter. Unless the criminal court issued a protective order granting the right to the property, the civil court would likely not consider the abuse as a defence against eviction. When a gender violence case is dismissed, this leaves the survivors unprotected against further post-separation legal intimidation and litigation abuses.

Gaps in the Laws in the UK

I wrote about gaps in the laws in the UK in my first self-published book. In cases of women who are in cohabiting relationships, who become wholly dependent on their partners during that relationship. Whose partners can move on quickly or have already replaced the significant person with another woman. Then walk away, leaving the discarded partner emotionally and financially devastated. What does the law say in these situations? Not very much, unfortunately. When a cohabiting relationship ends, the division of property and pensions is not covered by current laws in the UK or Spain.

The Law Commission in the UK had known about the inequity as far back as 2006 and published a consultation paper on cohabitation. There was the “Living Together Campaign” research published by the Ministry of Justice, and most of those surveyed felt strongly that the law should be changed so that cohabiting couples would have more rights. Yet, despite the commission of various reports and surveys, nothing changed. Or nothing changed in England and Wales, because if you reside in Scotland, the Family Law Act 2006 came into force in May of that year. The Act introduced entirely new rights for cohabitants in Scotland.

After the first version of my book was published, another attempt was made to change the laws around the rights of cohabiting partners. The Government response was published in October 2022. Unfortunately, the Government failed to provide any change in legislation that would offer a higher level of protection. Instead, they opted for a higher level of awareness raising. Leaving the onus on individuals to protect themselves.

Situation In Spain

And now I discover that a similar situation has existed in Spain. Legal professionals and advocates in Spain have been aware of the legal gap between property law and gender violence for at least two decades, with significant milestones and legal debates since the early 2000s. The issue I’ve raised is part of a broader, ongoing struggle to ensure that the Spanish legal system, particularly its civil and criminal divisions, works coherently to protect women from all forms of abuse.

Here is a timeline of key developments that highlight this “known gap”:

The Gender Violence Law (2004) The most significant event was the passage of Organic Law 1/2004 on Integrated Protection Measures against Gender Violence. This was a landmark law that created a specific framework to combat gender-based violence, establishing specialised courts and recognising psychological and economic abuse.

Before 2004: Women’s rights and feminist organisations had been lobbying for a comprehensive law since the early 1990s. The murder of Ana Orantes in 1997, a woman who spoke publicly about her abuse on television shortly before being killed by her ex-husband, was a catalyst that brought public and political attention to the issue.

The Laws Intent: Organic Law 1/2004 was designed to provide a legal shield for women. It was seen as a way to move beyond just physical violence and address the full spectrum of abuse, including psychological and economic. However, the laws implementation did not fully anticipate how abusers could use other legal tools, like property law, to continue their coercion.

The Rise of Precarious Eviction as a Weapon

As a result, since the mid-2000s, legal experts and women’s advocacy groups have increasingly documented how the “juicio de desahucio por precario” (precarious eviction trial) is being used as a strategic tool of economic abuse.

- Initial Focus: The initial focus of the gender violence law was on physical protection and restraining orders. The property and financial aspects were often relegated to separate civil or family courts, which were not equipped to handle them with a gender violence lens.

- The “Gap” Becomes Evident: The specific issue of abusers using precarious eviction as a form of post-separation abuse became a more prominent topic of debate and analysis. Lawyers and jurists began writing about the legal incongruity of a man, who had lived with a woman for many years, suddenly claiming she was a “precarious” occupant with no legal right to the home. They noted how this procedure, intended for squatters or guests, was being twisted to achieve a swift, legally sanctioned eviction of a partner, bypassing the more thorough (and time-consuming) family law process.

Recent Debates and Calls for Reform

In more recent years, particularly in the last decade, the debate has intensified.

- Recent Court Rulings: There have been legal efforts to challenge this. For example, some rulings have been appealed with the argument that a male property owner cannot simply evict a long-term cohabiting partner using the precarious eviction procedure, as their relationship established a different legal reality.

- Legislative Proposals: Advocates continue to push for legislative reform to either amend the civil procedure laws or strengthen the gender violence law to include provisions that prevent this kind of legal manipulation. The goal is to establish that a court, when a gender violence complaint has been filed, must consider the full context of the relationship and the potential for economic and psychological coercion.

Key Developments and Challenges

While the gap remains, there have been some attempts and ongoing efforts to address it:

- Judicial Rulings: Some courts are starting to show a greater awareness of the issue. A few jurisprudence (legal precedents) have emerged where judges, on a case-by-case basis, have ruled against a precarious eviction if it is proven to be an act of economic abuse. However, these are not widespread and do not form a consistent, binding precedent.

- Legislative Proposals: Women’s advocacy groups and legal experts continue to propose amendments to both the civil procedure laws and the gender violence laws to mandate that judges consider the full context of a relationship before granting an eviction order. There have also been recent legal measures to temporarily suspend evictions for vulnerable people, but these were often in response to broader social crises like the pandemic and do not specifically address the use of this law as a tool of abuse.

Within the Civil laws, I discovered Article 49 bis, which is about loss of jurisdiction in Civil cases where a Judge might suspect that there is a case of gender violence to be answered. I thought that I would be able to give my side of the story. I didn’t count on my public appointed defender silencing me by informing the Judge that she had no questions.

Civil Procedure Law Article 49 bis

Article 49 bis was added to the Spanish Civil Procedure Law (Ley de Enjuiciamiento Civil) through a legislative reform package in 2015. Specifically, it was introduced by Law 15/2015 of July 2, 2015, which focused on the reform of the Civil and Commercial Law.

This addition was a direct response to the “known gap” that legal professionals and advocates had been highlighting for years. The purpose of Article 49 bis is to create a legal mechanism that forces civil judges to yield jurisdiction to a specialised gender violence court if there are signs that the dispute is connected to a case of violence against a woman.

The article aims to ensure that:

- A civil judge cannot rule on a case (such as a precarious eviction) if there is a gender violence case pending or if a preliminary investigation has been initiated.

- The gender violence court, with its specialised knowledge and resources, is the proper venue to handle all aspects of the conflict, including those related to property and finances.

This legislative change was a significant step forward in attempting to prevent the kind of manipulation I had experienced, where a civil trial is used to bypass the protections offered by the gender violence laws. It demonstrates that the Spanish government and legal community recognised the problem and attempted to provide a legislative solution. But no use at all if the survivor on trial is not allowed to give her side of the story in a “Verbal Hearing” because she doesn’t understand or speak Spanish.

In short, while the legal framework has acknowledged and criminalised psychological and economic violence, the procedural mechanisms in civil law have not yet fully adapted to prevent the strategic use of eviction to perpetuate that abuse. The fight to close this gap is a crucial part of the broader effort to protect women from gender-based violence in all its forms.

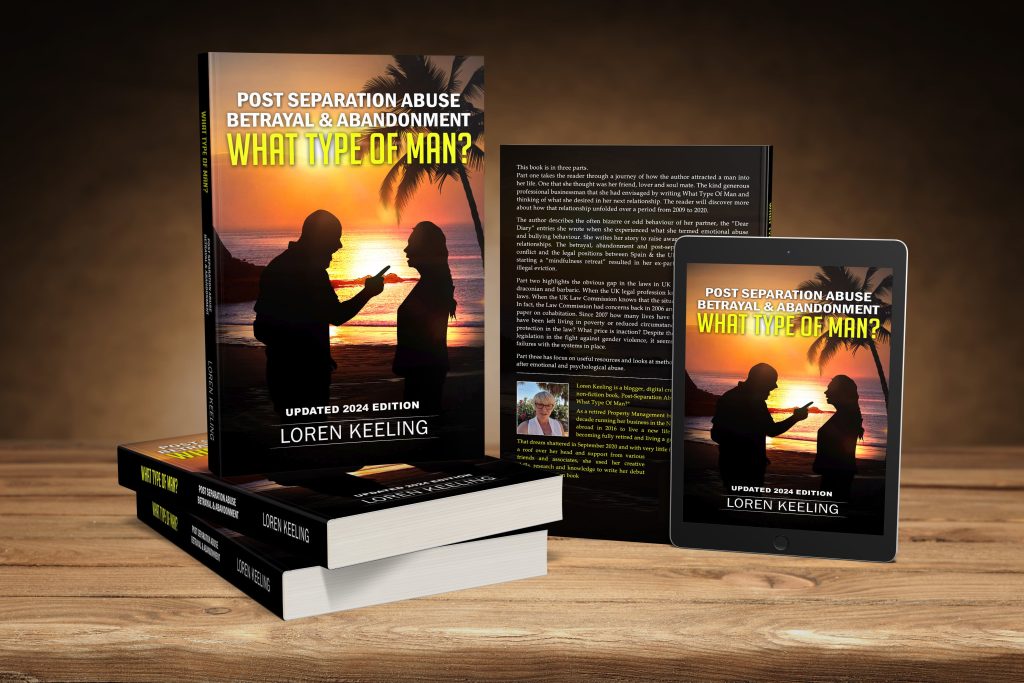

Self-Published Author – Loren Keeling (Pen Name)

My book was written while in the trauma of the threat of being made homeless in Spain. The initial legal advice I received was to stay in the property and negotiate, but that didn’t help me. The former person had already made it clear in a face-to-face meeting that I could not negotiate with him. He repeated a few times throughout that meeting that I could not negotiate with him. The second legal advice was from a private English-speaking Spanish lawyer. His advice was to file a gender violence complaint. I really didn’t want to file a complaint. I asked if he could write to the other lawyer. He told me, “Did you not hear what he said? You can not negotiate with him.” I had already been threatened, intimidated, humiliated, and discarded by the man I had been with for eleven years,

Things were moving quickly.

27th August 2020 – he terminated our relationship with a four-sentence discard speech.

29th August 2020 – he wrote out a letter that started “Dear Loren”, that offered a generous financial settlement of 50% of the value of the home, which he had termed a “GIFT”.

4th September 2020 – the house was on the market, and he had a call from the Agent I had appointed. I had met this woman locally.

The ex-partner came into the bedroom where I was keeping out of the way.

He came towards me and started shouting in my face, “Don’t fuck about with me. I’m in control. You do as I say, or I can throw you out onto the streets,” I was now being accused of saying something negative that would put people off buying the property. As soon as he left the room, I sent a WhatsApp to the Agent with the words, “Thanks a bunch, I’ve just been threatened”.

I sent a message to one of Phillips’ friends. I told him I had gone from feeling safe and secure, awaiting delivery of furniture, and thinking Phillip was ready to commit to our relationship, and now not knowing where I will go, or what I will do.

He sends the following text message in reply.

My Dearest Loren, I can’t help but feel that you have been shat on. Phillip assures me that he will look after you financially following the sale of the house, but until then, I can’t imagine how difficult it is to cope. You’ve got to be strong and think only of what’s best for you. It’s likely to be a few months (at best) before you receive any monies from the house.

I wish you all the strength in the world, and I think you are more than capable of doing really great things. You are bright and talented, strong and capable.

Fifth Anniversary Campaign. LifechangePlans. My Voice My Truth.

Buy The Book

Share The Story

Or Make A Donation